How to growers get the best use out of your biopesticide toolkit?

Author: Rachel Anderson

Author: Rachel AndersonAs Dr Andy Brown, secretary of the IBMA (International Biocontrol Manufacturers Association), and managing director of biological control specialist Andermatt UK, revealed: “The biocontrol market is growing at about 19% a year in the UK, compared to the synthetic chemical industry – [which is growing at] 2% or 3%. Admittedly, its starting at a smaller value but it shows you how much the industry is changing.” Brown was speaking at an AMBER (Application and Management of Biopesticides* for Efficacy and Reliability) event in Warwickshire, UK, earlier this year. Then, he pointed out that there are more, biological active ingredients being registered by European crop protection legislators than synthetic chemicals. From tougher safety rules to the evolution of resistance in target pests and diseases, there are many reasons why the availability of synthetic chemical pesticides is dwindling. Whilst there are now more biopesticides to choose from, growers are finding that these products can give inconsistent results. The University of Warwick’s Dr Dave Chandler, who is leading the five-year, Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (ADHB)-supported AMBER project, explained that the research is aiming to provide growers of protected (greenhouse) ornamental and edible crops with some of the underpinning knowledge they require. Chandler explained: “The crop type affects the development of the pest. On some types of crop the biopesticide will work better as it’s got longer to kill the pest because the crop slows down its development. We are dealing with a multiplicity of crop types. So, what we are doing in AMBER is using [and developing] mathematical models so that we can understand these processes, interact with the speed of development of the pest –and the biopesticides – so that we can identify optimum strategies for their use.”

“The right dose in the right place at the right time”

Having closely observed the practices of some growers, the AMBER team has so far confirmed that “timing is everything”. Chandler therefore advised growers to apply biopesticides “in the Goldilocks zone” – namely, when the conditions are “just right” (as was the temperature of the fictitiousbowl of porridge in the fairy tale Goldilocks.) Using powdery mildew control as an example, Chandler said: “You want to apply your biofungicide at exactly the right time. If there’s just a small amount of powdery mildew it [the product] will survive on the host. But if there’s too much mildew, it won’t be able to control it.”

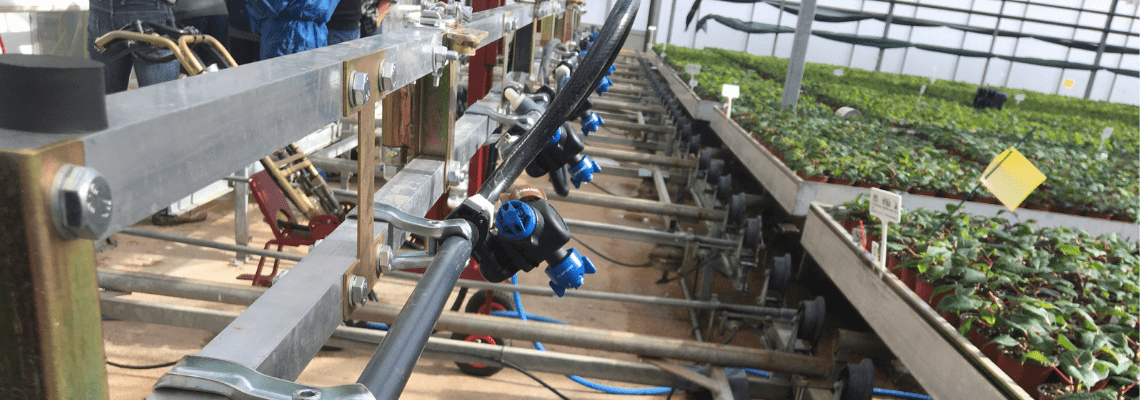

Another key observation is that growers must also “get the right dose in the right place at the right time.” Chandler explained that biopesticides are sensitive and can be damaged by chemical residues in spray tanks. “I’m going to moan at you. You are not checking your nozzles, cleaning your tanks, calibrating, or doing proper maintenance on your sprayers.” He added that applying the biopesticides at high volumes is causing run-off. “If you are not applying the correct volume you are wasting your product and that will result in inconsistency and lower efficacy.”

Clare Butler Ellis from the UK’s Silsoe Spray Application Unit emphasised that her trials for the AMBER project, which finishes next year (2020), found that water volumes greater than 100 litres per hectare did not improve the distribution of spray over the plant. Other advice to growers from the AMBER scientists includes storing these products correctly and, if they are unsure of their biopesticides’ compatibility with other elements of their integrated pest management (IPM) programme (such as beneficial insects), then it’s wise to leave as long an interval as possible between their application and their next introduction of predators.

They should carefully read the labels of their biopesticide products and speak to their supplier or manufacturer if they have any queries on when, and how best, to apply them.

* Biopesticides include products that are based on living organisms or natural substances, such as plant extracts and semiochemicals (such as insect sex pheromones).

.png?h=628&iar=0&w=1200)

.png?h=628&iar=0&w=1200)